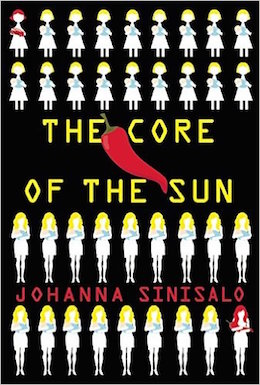

If one wants to write a story about social exclusion, Johanna Sinisalo explains in her 2012 essay “Weird and Proud of It,” one writes about a man turning into a giant cockroach, a.k.a. Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. What does it mean, then, when one—that is, Sinisalo herself—writes about a dystopian present in which women are catalogued and separated according to their varying levels of beauty and meekness, with clear homages to The Handmaid’s Tale and The Time Machine as well as its own unique, spicy aroma? You get the latest entry in “Finnish weird,” a subculture that Sinisalo describes as “the blurring of genre boundaries, the bringing together of different genres and the unbridled flight of imagination.”

Sinisalos’ imagination—which has previously turned to trolls and Moon-dwelling Nazis—is certainly airborne in The Core of the Sun: In 2016, the Eusistocratic Republic of Finland is devoted to maintaining the health and well-being of its citizens. Problem is, that means preserving the divide between pretty, childlike eloi and the smarter, unfeminine morlocks; one makes an ideal little housewife, while the other is sent to the fields so her big ideas won’t strain her sister’s weak mind. Like Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale, our narrator is Vanna, a young woman who looks and acts like an eloi but, thanks to a quirk in evolution, is secretly a morlock. Searching for her missing eloi sister Manna, she must nevertheless keep her cover in place, while fighting off the alluring pull of the dark Cellar in her mind. Her only defense against the icy rising waters of the Cellar are occasional hits of hot peppers, to which she has become hopelessly addicted.

That’s right—the Eusistocratic Republic of Finland is so obsessed with utter blandness that it has outlawed tobacco, alcohol, and capsaicin. (Dark chocolate is OK, because of its high antioxidants.) That last detail is part of what makes The Core of the Sun so endearing because of how weird it is. Yes, there are people who are horribly allergic to capsaicin, but it’s difficult to imagine it held up in the same category as cocaine and heroin. But that’s the point: It should be insane that women are separated into such a clear dichotomy, but we’ve had the Madonna/whore complex since longer than anyone can remember.

One of the most chilling takeaways from Margaret Atwood’s dystopian classic is how the women, separated by castes, never unite—partly because of men’s totalitarian control, yes, but also due to the competition fostered by the hierarchy. The Wives sneer at the Handmaids because they get fancy husbands, but mostly it’s to cover their shame at being infertile; the Aunts probably think they’re better off than either class, seeing as they’re allowed to read and write, and all they have to do is train the next generation of Handmaids; and so forth. So it is among the elois: They’re taught from a young age to cultivate shallow friendships for the sake of climbing over each other in their stiletto heels for the affection of a masco. Any imperfection or issue an eloi possesses is to her peers’ advantage.

And in pretending to be an eloi—a shepherd girl in a princess’ gown, as her grandmother Aulikki encourages her—Vanna unwittingly engenders this same rivalry with Manna. Sweet, idiotic Manna, who has been conditioned to want nothing more than a lavish, white wedding. Through letters that Manna may never have the chance to read (not least because she can’t handle anything more complex than a Femigirl magazine, but also because of her unknown whereabouts), Vanna spins out the tale of their fraught childhood, of copying her younger sister to fit in while scheming a way to wriggle out of the system. While these portions of the novel are a bit over-expository, the depth of emotion is there: Vanna’s fierce protectiveness only serves to turn Manna against her, especially where their masco friend Jare is concerned.

It’s Jare with whom Vanna spends the majority of the story, beginning in 2016: The two have quite a business going as capsaicin dealers, what with Vanna’s ingenious utilization of her double life as an eloi. It grants her far more access than anyone would guess in this dystopian state, where elois can roll around in bushes with paramours and stumble into seedier parts of town, all because these airheads couldn’t possibly think about anything but wedding gowns and home-cooked dinners. Having developed quite the tolerance as an addict, Vanna also comes up with a shrewd test of the stuff’s true power: applying a swipe beneath her underwear, because “the lower lip doesn’t lie.” See what I mean about the potency of such particular details? Having dabbled in my fair share of SFF in my own plays, I’ve come to the realization this year that the most affecting speculative fiction stories are the ones that favor the specific experience over the universal one. Of course a woman who has a complicated and mostly unpleasant relationship to sex would literally turn up the heat in her own genitals in order to test the one substance that actually gives her life.

As savvy as they are, Vanna and Jare meet the missing piece of their puzzle in the Gaians, hippies who “offer warmth and love”—meaning, homegrown peppers and the Core of the Sun, a hybrid that chili with a scoville count so high it’s rumored to cause hallucinations. Will this search for enlightenment bring Vanna closer to her missing sister, or widen the gap between them? While it’s laughable at first thought that a dystopian story centers its action around raids on chili pepper gardens, Sinisalo brings the same sense of paranoia and urgency created by the Eyes in the Republic of Gilead.

Thanks to television series and comics like Jessica Jones, Bitch Planet, and You’re the Worst, among others, 2015 really was the year of mental illness getting the kind of attention it deserves. I’d like to add The Core of the Sun to that list, for how it depicts Vanna’s depression through the Cellar: a dark, damp corner of her mind, where water sloshes over everything and threatens to drown her with every thought of Manna. For all of the over-the-top worldbuilding that creates the scaffolding of this book, it’s simple metaphors like this that ground the reader.

So, what prompts a Finnish weird writer to combine transcendental chilis, dank Cellars, eugenics, wedding culture, and the joys of gardening into a stew not unlike the one in which Vanna tastes her first hit of capsaicin? Because thirty years after Offred illicitly recorded her tale on tape cassettes, we still need stories of the horrors exerted on women: their bodies molded into “ideal” forms and used for pleasure (but never their own) or procreation. If it takes the shock of a hot pepper slid into a vagina to spark the debate, then so be it.

The Core of the Sun is available January 5 from Grove Atlantic.

Natalie Zutter loves eating pickled jalapeños straight from the jar, but will definitely look at things differently the next time she has a craving. You can read more of her work on Twitter and elsewhere.